Abstract

In 2019, the Canadian Government released a national dementia strategy that identified the need to address the health inequity (e.g., avoidable, unfair, and unjust differences in health outcomes) and improve the human rights of people living with dementia. However, the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is having an inequitable impact on people with dementia in terms of mortality and human rights violations. As the new Omicron COVID-19 variant approaches its peak, our commentary highlights the need for urgent action to support people living with dementia and their care partners. More specifically, we argue that reducing COVID-19 inequities requires addressing underlying population-level factors known as the social determinants of health. Health disparities cannot be rectified merely by looking at mortality rates of people with dementia. Thus, we believe that improving the COVID-19 outcomes of people with dementia requires addressing key determinants such as where people live, their social supports, and having equitable access to healthcare services. Drawing on Canadian-based examples, we conclude that COVID-19 policy responses to the pandemic must be informed by evidence-informed research and collaborative partnerships that embrace the lived experience of diverse people living with dementia and their care partners.

Résumé

Dans sa stratégie nationale sur la démence publiée en 2019, le gouvernement canadien définissait le besoin de redresser les iniquités en santé (p. ex. les différences évitables, inéquitables et injustes dans les résultats cliniques) et de mieux faire respecter les droits humains des personnes vivant avec la démence. La pandémie de la nouvelle maladie à coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) touche cependant de façon inéquitable les personnes atteintes de démence sur le plan de la mortalité et des violations des droits humains. À l’heure où le nouveau variant Omicron de la COVID-19 est sur le point d’atteindre son pic, nous faisons valoir qu’il faut appliquer des mesures urgentes pour aider les personnes vivant avec la démence et leurs partenaires soignants. Plus précisément, pour atténuer les effets inégaux de la COVID-19, il faut aborder les facteurs populationnels sous-jacents – les déterminants sociaux de la santé. Les disparités de l’état de santé ne peuvent pas être corrigées par la simple observation des taux de mortalité chez les personnes atteintes de démence. Nous croyons donc que pour améliorer les résultats cliniques de la COVID-19 chez ces personnes, il faut aborder les grands déterminants comme leurs milieux de vie, leurs soutiens sociaux et l’équité d’accès aux services de soins de santé. À partir d’exemples canadiens, nous concluons que les interventions stratégiques contre la pandémie de COVID-19 doivent être éclairées par des études fondées sur des données probantes et par des partenariats de collaboration qui tiennent compte du vécu de toutes sortes de personnes vivant avec la démence et de leurs partenaires soignants.

Similar content being viewed by others

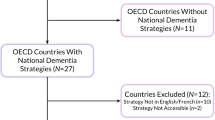

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is having an inequitable and disproportionate impact on people living with dementia. In Canada, statistics show that dementia is the most common co-morbidity, accounting for 36% of all COVID-19-related deaths (O’Brien et al., 2020). Moreover, a growing number of reports highlight human rights violations against people with dementia related to inequitable access to healthcare services, life-saving resources, health information, social connection, palliative services, and end-of-life care (Banerjee & Estabrooks, 2021; Bethell et al., 2021; Kaasalainen et al., 2021; Mialkowski, 2020; Suárez-González et al., 2020).

Despite this knowledge, there has been little action from policymakers to improve both the health equity and the human rights of people living with dementia. As the new Omicron COVID-19 variant approaches its peak, there is an urgent need to address issues of health inequity in COVID-19 health outcomes for people with dementia. Health inequity refers to avoidable, unnecessary, and unfair differences in health outcomes between different population groups (Whitehead, 1992). Compared with other groups, people with dementia have experienced the highest COVID-19-related mortality rates (ADI, 2020; O’Brien et al., 2020). Although some researchers warn that COVID-19 could increase the prevalence of dementia through neurological symptoms associated with long COVID-19 (e.g., long-haul COVID-19), this commentary focuses specifically on people diagnosed and living with dementia as it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the effects of long COVID-19. Drawing on Canadian-based examples, we argue that reducing COVID-19 inequities for people with dementia requires addressing underlying population-level factors known as the social determinants of health. Health disparities cannot be rectified merely by looking at morbidity and mortality rates of people with dementia. Thus, we believe that improving COVID-19 outcomes for people with dementia requires addressing key determinants such as where people live, their social supports, and their access to healthcare and support services.

Physical environment: living conditions

Attention to inequitable health outcomes related to living conditions is essential to understanding the COVID-19 impact on people with dementia. For example, a report by the Government of Canada (2020) found that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated issues experienced by people with dementia in long-term care facilities, such as overcrowding, understaffing, limited resources (such as personal protective equipment, and COVID-19 testing), no national training standards for long-term care workers, and inadequate space (e.g., shared bedrooms, bathrooms, and dining areas) to mitigate the transmission of the COVID-19 virus. Similarly, a report by Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer (Tam, 2020) notes that people in long-term care homes face a disproportionate risk of contracting COVID-19 because of insufficient COVID-19 testing and personal protective equipment, worker shortages, limited physical proximity in shared rooms, and precarious work environments and staff who work at multiple long-term care homes. Consequently, by May 2020, more than 840 outbreaks were reported in Canadian long-term care facilities and retirement homes, accounting for more than 80% of all COVID-19 deaths in the country (CIHI, 2020).

The right to the highest attainable standard of health is a fundamental human right that is enshrined in international human rights laws (United Nations, 2006). However, health is also influenced by other human rights such as access to adequate housing, safe drinking water and sanitation, and nutritious foods. Recently, the Canadian Armed Forces released a report based on the COVID-19 conditions in five long-term care homes, detailing residents being denied food, forced confinement, cockroach infestations, residents left in soiled diapers, unwarranted sedation, poor COVID-19 infection control measures, and suspected abuse of residents, including one case in which staff may have contributed to a resident’s death due to choking (Mialkowski, 2020). These issues detrimentally impact and infringe on the human rights of people with dementia, and the United Nations (2006) convention on the rights of persons with disabilities, including the right to health (Article 25) and the right to life (Article 25). Steele et al. (2020) assert that care facilities have become COVID-19 prisons, where people with dementia are not allowed visitors and are often confined to their rooms. Specifically, the authors highlight such similarities between prisons and long-term care facilities as confinement, mechanical constraints, and pharmaceutical sedation. Peisah et al. (2020) note that the quality of life and end-of-life care in both settings have been inadequate, with human rights issues relating to limited access to healthcare, autonomy, and dignity.

Recently, the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (2021) released its first significant decision on a visitation ban in disability-related accommodation and the applicability of an individual’s human rights during the COVID-19 pandemic. In JL v. Empower Simcoe, the Tribunal found that the visitation ban, which was created as a COVID-19 infection control measure, discriminated against and adversely impacted the individual’s human rights (Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, 2021). This decision highlights that the pandemic is not appropriate justification for failing and/or refusing to adequately accommodate persons who require disability-related accommodation, including people with dementia. Consequently, research shows that COVID-19 visitation bans in long-term care facilities have had severe implications for people with dementia in terms of physical and mental health, diminishing social connections, undermining quality of life, and challenging the human rights of people with dementia in long-term care (Iaboni et al., 2022). As such, it is essential that policymakers be vigilant in avoiding infection control measures that violate the human rights of people with dementia.

Restricted social support

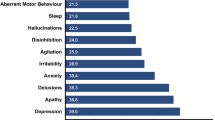

Given the highly transmissible nature of COVID-19, provincial governments across Canada have imposed infection control measures such as lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, visitation bans, confinement measures, and physical distancing orders. However, research shows that social support is a basic human need, especially for people living with dementia in long-term care facilities (Bethell et al., 2021; Bacsu et al., 2021a; Iaboni et al., 2022). People with dementia have identified that loneliness can lead to feelings of abandonment and diminish one’s quality of life (O’Rourke et al., 2015). Recently, a systematic review of the literature identified that infection control measures are contributing to mental health challenges experienced by people with dementia, such as anxiety, depression, agitation, loneliness, irritability, sleep disorders, cognitive decline, and feelings of hopelessness and despair (Bacsu et al., 2021b). Research shows that social isolation and loneliness in the COVID-19 context are major risk factors linked to poor physical health status, such as increased heart disease, blood pressure, stroke, obesity, diminished immune system, decreased cognition, and mortality (Wu, 2020). Accordingly, COVID-19 infection control measures (e.g., visitation bans, confinement, and stay-at-home orders) may have increased the risk of hospitalizations, cognitive deterioration, and mortality among people with dementia (Suárez-González et al., 2020). It is essential that policymakers balance infection control policies with the human rights of people living with dementia.

Inequitable access to healthcare and support services

Access to healthcare and support services plays a critical role in the health equity and the human rights of people with dementia and their care partners. During the pandemic, Suárez-González et al. (2020) assert that the human rights of people with dementia are being compromised by structural barriers and discriminatory practices, such as the limited provision of healthcare services and life-saving resources (e.g., physician visits, specialist services, health information, palliative care services, oxygen therapy, diagnostic services, and end-of-life care). In Canada, Banerjee and Estabrooks (2021) note that long-term care residents, including people with dementia, and staff were often last in line for COVID-19 testing and last to receive personal protective equipment, and that long-term care residences were directed not to send their residents to hospitals in order to keep the hospital beds open for others. Similarly, a report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (2021) found that, compared to pre-pandemic years, people with dementia in long-term care homes experienced decreased physician visits, reduced access to specialist services, an increased use of antipsychotic drugs, and reduced hospital transfers for illness and infection (CIHI, 2021). Kaasalainen et al. (2021) note that the surge of COVID-19 and rationing of healthcare resources have intensified the pre-existing need for improvements in palliative services and end-of-life care for people with dementia. However, this absence of equitable access to healthcare services for people with dementia has led to unnecessary suffering and loss of life (Peisah et al., 2020). It is essential that people with dementia are not discriminated against and that they receive equitable access to healthcare services such as physician visits, specialist services, hospital transfers, intensive care units, health information, palliative care services, and end-of-life care during the pandemic and beyond.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is taking a serious toll on people with dementia. Moreover, the human rights and fundamental needs of people with dementia are being compromised. Although the national dementia strategy of Canada (Government of Canada, 2019) highlights the need to protect the human rights of people with dementia, there has been little action to address the human rights and the health equity of people with dementia during the pandemic. Rather, policymakers have used a one-size-fits-all approach to COVID-19 policy that has consisted of lockdowns and visitation bans. Drawing on Canadian-based examples, we have argued that improving COVID-19 outcomes for people with dementia requires actions to address key social determinants of health.

First, we believe that immediate actions are necessary to address structural inequalities and improve the living conditions in long-term care facilities for people with dementia (Banerjee & Estabrooks, 2021; Bethell et al., 2021; CIHI, 2021). Specifically, actions are needed to address issues of overcrowding, enhance care home inspections, ensure timely access to specialist/physician services, provide national dementia training standards for staff, and develop a crisis management plan for COVID-19 outbreaks with adequate personal protective equipment, rapid testing, and contact tracing in long-term care facilities. In addition, there is a growing need for leadership from the federal government to develop a long-term care strategy with provincial/territorial coordination to ensure safeguards, national training standards, and financial incentives/supportive resources to recruit and retain staff, as well as to provide a monitoring framework and measures of accountability to protect the human rights of people with dementia.

Second, interventions are needed to improve social support for people with dementia during the pandemic. For example, studies show that social isolation has negatively impacted the mental, cognitive, and physical health of people with dementia (Bacsu et al., 2021a; Bethell et al., 2021; Iaboni et al., 2022). Consequently, there is a growing need for more evidence-informed research on interventions to foster social support (e.g., essential visitor programs, social support programs, and mental health programs) informed by lived experience and collaborative partnerships to ensure maximum impact. In addition, policymakers must ensure that infection control policies (such as visitation bans, confinement orders, lockdowns, and stay-at-home orders) do not discriminate against and violate the human rights of people living with dementia.

Third, interventions are necessary to address discriminatory practices and structural barriers to accessing healthcare and support services (such as limited access to specialist services, hospital transfers, palliative care services, health information, physician visits, and end-of-life care) for people with dementia (Banerjee & Estabrooks, 2021; Kaasalainen et al., 2021). More specifically, safeguards and formal policies are critical to ensuring that healthcare protocols and guidelines do not stigmatize and/or discriminate against people with dementia with respect to accessing healthcare and life-saving services (Suárez-González et al., 2020). For example, research shows that people with dementia are often stigmatized, homogenized, and stereotyped as being a highly vulnerable group of people who are near the final stages of their life (ADI, 2019; Oscar et al., 2017; WHO, 2012). However, dementia does not progress in a linear fashion and impacts people differently (Gallagher, 2019). It is vital that policymakers and clinicians understand that people with dementia are diverse and able to live meaningful lives. Consequently, people with dementia and their care partners must be included in policy discussions on COVID-19 responses, especially around the provision of medical services and lifesaving resources.

Conclusion

Urgent action is needed to improve the health equity and the human rights of people with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, addressing these issues is neither a straightforward nor a simple endeavour. More specifically, we have argued that improving COVID-19 outcomes requires actions to address not only biomedical determinants but also key social determinants of health such as where people live, their social supports, and access to healthcare and support services. Additionally, we believe that federal leadership is needed to support government coordination at the provincial/territorial levels to ensure safeguards, supportive resources, national standards, and measures of accountability to uphold the human rights of people with dementia. Moreover, we argue that people with dementia and their care partners must be recognized as key stakeholders in policy discussions on COVID-19 responses, especially around the provision of medical services and lifesaving supports. Unless action is taken to address COVID-19 disparities at the population level, health inequities and human rights issues faced by people with dementia will continue to grow. Moving forward, policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic must be informed by evidence-informed research and collaborative partnerships that embrace the lived experience of people living with dementia and their care partners.

Data availability

Not applicable

Code availability

Not applicable

References

Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2019). World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to dementia. 27 Dec. 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2019/

Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2020). COVID-19 deaths disproportionately affecting people with dementia, targeted response urgently needed. 1 Sept. 2020. Retrieved from, https://www.alzint.org/news/covid-19-deaths-disproportionately-affecting-people-with-dementia/

Bacsu, J., O’Connell, M., Cammer, A., Grewal, K., Green, S., Poole, L., Azizi, M., & Spiteri, R. (2021a). Using Twitter to understand the COVID-19 experiences of people with dementia: Infodemiology study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(2), e26254. https://doi.org/10.2196/26254

Bacsu, J., O’Connell, M. E., Webster, C., Poole, L., Wighton, M. B., & Sivananthan, S. (2021b). A scoping review of COVID-19 experiences of people living with dementia. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 112(3), 400–411. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00500-z

Banerjee, S. & Estabrooks, C. (2021). Long-term care outbreaks, deaths reveal how badly we undervalue seniors and people with dementia. 31 Dec. 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/opinion-dementia-long-term-care-homes-1.5871981.

Bethell, J., O’Rourke, H. M., Eagleson, H., Gaetano, D., Hykaway, W., & McAiney, C. (2021). Social connection is essential in long-term care homes: Considerations during COVID-19 and beyond. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 24(2), 151–153. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.24.488

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2020). Pandemic experience in the long-term care sector: How does Canada compare with other countries. Ottawa, ON: CIHI. 27 Dec. 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/covid-19-rapid-response-long-term-care-snapshot-en.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on long-term care in Canada: Focus on the first 6 months. Ottawa, ON: CIHI. 31 Dec. 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/impact-covid-19-long-term-care-canada-first-6-months-report-en.pdf

Gallagher, R. (2019). The lived experience of people with dementia. BCMJ, 61(1), 39–40.

Government of Canada. (2019). A dementia strategy for Canada: Together we aspire. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada, 2019. 14 Sept. 21. Retrieved from, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/dementia-strategy.html

Government of Canada. (2020). Long-term care and COVID-19. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada, 2020. 18 Aug. 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/063.nsf/eng/h_98049.html

Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario. (2021). JL v. Empower Simcoe, 2021 HRTO 222 (CanLII). 20 Sept. 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onhrt/doc/2021/2021hrto222/2021hrto222.html.

Kaasalainen, S., Mccleary, L., Vellani, S., & Pereira, J. (2021). Improving end-of-life care for people with dementia in LTC homes during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 24(3), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.24.493

Iaboni, A., Quirt, H., Engell, K., et al. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to person-centred infection prevention and control: Results of a survey about the Dementia Isolation Toolkit. BMC Geriatrics, 22(74). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02759-4

Mialkowski, C. J. J. (2020). OP LASER JTFC observations in long-term care facilities in Ontario. Toronto. 14 Feb 21. Retrieved from, http://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6928480-OP-LASER-JTFC-Observationsin-LTCF-in-On.html.

O’Brien, K., St-Jean, M., Wood, P. Willbond, S., Phillips, O., Currie, D. and Turcotte, M. (2020). COVID-19 death comorbidities in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada. 20 Sept. 2021. Retrieved from, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00087-eng.htm

O’Rourke, H. M., Duggleby, W., Fraser, K. D., & Jerke, L. (2015). Factors that affect quality of life from the perspective of people with dementia: A metasynthesis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13178

Oscar, N., Fox, P. A., Croucher, R., Wernick, R., Keune, J., & Hooker, K. (2017). Machine learning, sentiment analysis, and tweets: An examination of Alzheimer's disease stigma on Twitter. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(5), 742–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx014

Peisah, C., Byrnes, A., Doron, I. I., Dark, M., & Quinn, G. (2020). Advocacy for the human rights of older people in the COVID pandemic and beyond: a call to mental health professionals. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(10), 1199–1204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220001076

Steele, L., Carr, R., Swaffer, K., Phillipson, L., & Fleming, R. (2020). Human rights and the confinement of people living with dementia in care homes. Health and Human Rights, 22(1), 7–19.

Suárez-González, A., Livingston, G., Low, L.F., Cahill, S., Hennelly, N., Dawson, W.D., Weidner, W., Bocchetta, M., Ferri, C.P., Matias-Guiu, J.A., Alladi, S., Musyimi, C.W., Comas-Herrera, A. (2020). Impact and mortality of COVID-19 on people living with dementia: Cross country report. 2020, CPEC-LSE. Retrieved from, https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/International-report-on-theimpact-of-COVID-19-on-people-living-with-dementia-19-August-2020.pdf

Tam, T. (2020). From risk to resilience: An equity approach to COVID-19. Public Health Agency of Canada. 19 Nov 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19.html

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). United Nations: Office of the High Commissioner, Human Rights. 14 Sept 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CRPD/Pages/ConventionRightsPersonsWithDisabilities.aspx

Whitehead, M. (1992). The concepts and principles of equity and health. International Journal of Health Services: Planning administration, evaluation, 22(3), 429–445.

World Health Organization. (2012). Overcoming the stigma of dementia. 30 Dec. 2021. Retrieved from, https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf

Wu, B. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Global Health Research and Policy, 5(27). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA). CCNA is supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) with funding from the following partners: the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, the Centre for Aging and Brain Health, the Alzheimer Society of Canada (ASC), and the CIHR Institute of Indigenous Peoples’ Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JDB drafted the commentary with the support of MEO and MBW. All the authors provided feedback and reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bacsu, JD.R., O’Connell, M.E. & Wighton, M.B. Improving the health equity and the human rights of Canadians with dementia through a social determinants approach: a call to action in the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Public Health 113, 204–208 (2022). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-022-00618-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-022-00618-8